CLEMSON — A groundbreaking recently at Clemson University signals both the spot where a new historical marker will be erected and the launch of a new commitment to tell the university’s full history.

As two descendants of people once enslaved at Fort Hill watched, university officials, trustees and special guests broke ground for a historical marker that will commemorate a site where slave quarters stood on the plantation owned by John C. Calhoun and later by university founder Thomas Green Clemson. (See photo album from the event.)

“The story of Clemson University’s founding is one of great vision, commitment and perseverance,” said Clemson President James P. Clements. “However, it is also a story with some uncomfortable history. And, although we cannot change our history, we can acknowledge it and learn from it, and that is what great universities do.”

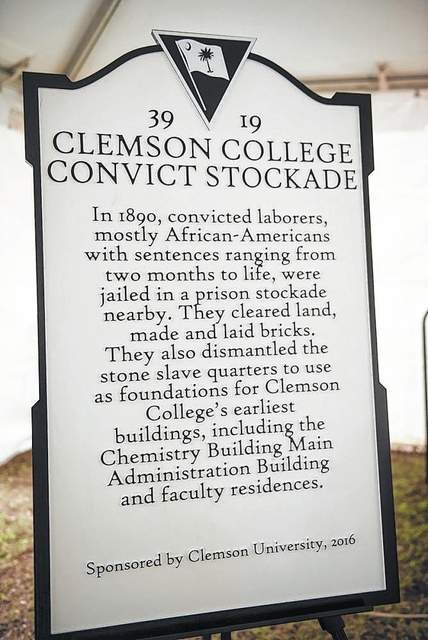

One side of the marker that will be erected at the intersection of South Palmetto Boulevard and Fernow Street Extension notes that 70 to 80 enslaved African-Americans lived at Fort Hill in 1849, the date of the earliest known written description of the slave quarters, with the number rising to 139 by 1865. The other side of the marker indicates that a nearby site was later used for a stockade to house convict laborers, most of them African-American, who cleared land and helped build some of the university’s first buildings.

Another historical plaque will be erected at the Calhoun Bottoms farmland to commemorate the role of Native Americans and African-Americans in the development of the Fort Hill Plantation lands. A third will be placed at Woodland Cemetery to mark the burial sites of the family of John C. Calhoun, slaves and state-leased prisoners who died during their confinement at Clemson.

The markers are one way Clemson is working to give a more complete and accurate public accounting of its history in the wake of a national movement on university campuses to acknowledge connections to slavery, segregation or other practices and viewpoints inconsistent with current institutional values.

In July 2015, trustees appointed a task force to work with the administration to gather input from a wide variety of constituents and recommend ways to tell the full story of Clemson’s history, good and bad. The board approved the report of the task force in February.

“The task force was gratified by the outpouring of ideas and perspectives submitted online, in meetings and through direct mail,” said Task Force Chair David H. Wilkins. “The clear, consistent message was that Clemson must tell its complete, though imperfect, story. While the work of the task force is complete, our efforts to tell the full story are just beginning.”

In his remarks, Clements praised the work of two individuals who were the driving force behind the work that led to today’s groundbreaking: Rhondda Robinson Thomas, associate professor of English whose research on African-Americans who lived and labored at Clemson prior to desegregation spurred interest in the markers, and alumnus James E. Bostic Jr., whose $50,000 donation helped fund Thomas’ work. Bostic was the first African-American to earn a doctorate from Clemson.

“We are indebted to Dr. Thomas for her efforts to discover these untold stories and make sure they are told,” Clements said. “And we are extremely grateful to Dr. Jim Bostic and his wife, Edith, for their continued support of Clemson and the work of our faculty.”

One of those stories is about Sharper and Caroline Brown, whose daughter Matilda was born into slavery but lived most of her life as a free woman. Matilda Brown’s granddaughter, Eva Hester Martin of Greenville, was a guest at the groundbreaking ceremony, accompanied by her husband, John Martin, and daughter and son-in-law Valerie Martin-Lee and Lorenzo Lee. Along with the groundbreaking, Mrs. Martin was celebrating her 90th birthday.

It’s a story Thomas is piecing together from personal recollections backed up by photos, newspaper clippings, church and census records and other documentation.

Mrs. Martin’s story has a happy ending, Thomas said. The youngest of 10 children, she earned a degree in chemistry from S.C. State University, enjoyed a successful career as a medical technician in Chicago and Los Angeles and raised four children.

“These are stories of overcoming obstacles, and it’s that same narrative that can still inspire and uplift people today,” she said. “Some of these stories make us proud, some make us think and some make us cringe, but they all have lessons we can learn.”

Collecting and telling those stories involves a lot of listening, followed by painstaking efforts to locate official records and documents, which are often spotty.

“Our archives are a wonderful resource, and census records are a great help,” she said. “For the convict laborers, however, the pardon records provide the strongest evidence of the men and boys who labored at Clemson, as the documentation specifies when they were released from Clemson College. But in some cases the records are incomplete or missing. I’m also researching their lives prior to and after incarceration to provide important insights into their experiences as members of families and communities.”

Thomas hopes the university’s efforts to tell these stories will encourage more family members to come forward with information, photos, family Bibles or other materials that can confirm an ancestor’s connection to the university’s early years.

“There are many universities struggling with how to confront an uncomfortable past, and Clemson has the opportunity to become a national model for how to create a more inclusive history,” she said.